3 Marginalia in the Archive

3.1 The Historiography of Marginalia

Marginalia have been recognized as significant by scholars since as early as the 19th century, who used them as a means to construct the history of earlier scholars in more detail and to expand upon their published works. Particularly of note from this time was the work of literary scholar George Charles Moore Smith. In 1913 he published a book that aimed to “illustrate the life, character, and opinions” of early modern writer Gabriel Harvey using his “unpublished materials”, citing Harvey’s vast array of marginalia in this process of extending existing knowledge.7 More current works tend to focus on the materiality of marginalia, using a combination of their content alongside their placement and material features of the book itself to analyze how early modern readers interacted with and used literature.8

One of the earlier modern seminal works in the history of reading, ““Studied for Action”: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy” by historians Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton, expands further on the notes produced by Gabriel Harvey to establish marginalia as an intellectual method through microscopic analysis of his annotations inserted into Livy’s ancient history of Rome.9 The article highlights Harvey’s active and purposeful approach to reading, characterized by his meticulous marginalia and extensive annotations. Through an analysis of Harvey’s notes and markings, Jardine and Grafton reveal how Harvey used Livy’s texts as a foundation for his own intellectual pursuits, employing them to shape his ideas, compositions, and refine his own writings.10 Harvey’s annotations not only offer insights into his personal interpretations of Livy’s works but also demonstrate his scholarly engagement and his desire to apply the lessons learned from ancient history to contemporary political and cultural contexts. By examining Harvey’s reading practices and how he interacted with Livy’s texts, the article illustrates the active role of early modern scholars in constructing knowledge and engaging with classical literature for practical and intellectual purposes.

Moving beyond the study of past scholars, historian Heidi Brayman Hackel established the foundations of marginalia “as records of reading motivated by cultural, social, theological, and personal inclinations” through shifting the focus from professional scholars such as Harvey to the more casual reader.11 In this defining work on the history of reading, Reading Material in Early Modern England seeks to “delineate the asymmetries of early modern English literacies and reading habits and to expand the category of readers to include a greater variety of English people”; Brayman Hackel accomplishes this by offering a comprehensive examination the social, cultural, and intellectual contexts in which reading took place, providing insights into the reading practices of different members of society, including women, artisans, and the elite through the analysis of annotated texts in multiple formats.12 Through extensive research and select case studies ranging from the library of Lady Anne Clifford to unspecificed annotators present in copies of Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, Brayman Hackel delves into the materiality of texts, investigating the physical aspects of books and how they influenced reading experiences. She explores the use of illustrations, typography, and paratextual elements, demonstrating how these features shaped readers’ interactions with the texts. Through further investigation into print culture, the emergence of the printing press, and the significance of libraries, bookshops, and private collections in shaping access to and availability of reading materials, Brayman Hackel also addresses the impact of censorship and the control of reading materials by established institutions such as Oxford’s Bodleian Library and the authorities.13 By extension, Brayman Hackel also examines the purposes of reading in early modern England, ranging from religious and moral instruction to entertainment and leisure. Through this exploration, she counters the fiction of “a singular ideal reader ungrounded in place or time” and instead creates “a portrait of an early modern ‘gentle reader’ alongside fragmentary glimpses of multiple readers at single moments in their reading lives.”14 Through emphasis on the importance of reading as a cultural and social practice and its impact on knowledge production, relationships, and the formation of early modern English society, Reading Material in Early Modern England contributes to our understanding of the broader historical and cultural significance of reading during this period, offering valuable insights into the ways in which texts were consumed, understood, and used in early modern English society.

Closely following Brayman Hackel’s publication was the release of Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England by William H. Sherman; Sherman’s work diverged from the case study model Brayman Hackel follows common in the history of reading, in that he chose to focus on collections of annotated books for his case studies rather than on individual readers or books. Through the isolated traces upon which his book rests, Sherman’s analyses yield “some larger patterns and a more systematic sense of how a wider group of readers used a wider range of books than in previous accounts of pre-modern marginalia.”15 By analyzing the marginalia of readers who left behind “substantial annotations”, Sherman uncovers the diverse motivations behind readers’ interactions with books, how these marks provide insights into the readers’ responses, interpretations, and both private and public connections with the text. Like Brayman Hackel, Sherman explores how these markings can reveal readers’ social identities, scholarly disciplines, and cultural values. However, unlike Brayman Hackel, Sherman focuses more of his analysis not only on content of the marginalia, but the materiality of the text which this marginalia is present in, “putting books alongside the other objects…to reconstruct the material, mental, and cultural worlds of our forebears.”16 Throughout the book, he pays close attention to “patterns of use” such as bindings, repairs, and other signs of wear, which offer further clues about the history of ownership, as well as early modern reading habits and the networks of exchange and circulation that facilitated the dissemination of ideas through books. Further, Sherman considered how the trade of “used” books functioned, the availability and affordability of texts, and the significance of book ownership in the cultural and intellectual life of the time, concluding that “Renaissance readers have much to teach us not only about the uses of books in the past but also about attitudes toward books where the past meets the present.”17

Uniting the work of marginalia as records of reading by Brayman Hackel and of material affordance by Sherman is Stephen Orgel, whose The Reader in the Book: A Study of Spaces and Traces examines individual acts of reading by examining books in which the text and marginalia are “in intense communication with each other, glossing, correcting, reminding, emphasizing, arguing — cases in which reading constitutes an active and sometimes adversarial engagement with the book.”18 However, in tandem with this Orgel focuses more intensely on the book’s materiality than Brayman Hackel, here echoing Sherman’s work, exploring the physical and conceptual spaces created within books and the traces left there by readers, offering an analysis of how reading practices have evolved across the early modern period. Drawing both upon works that are considered early modern literary classics in the present as well as books that were considered classics in their own time, Orgel delves into the concept of reading as writing, the way readers absorb the texts they annotate. He explores the physicality of books, including their size, format, and design, and how these factors shape the reading and by extension annotating experience. Like Brayman Hackel, The Reader in the Book delves into the social and cultural aspects of reading, examining how readers’ identities, backgrounds, and personal experiences influence their engagement with literature. Each chapter of Orgel’s work considers factors such as gender, class, and education, highlighting the diverse ways in which readers approach and unravelled texts. He joins the discussion of materiality and content through understanding how the book itself was conceptualised during the early modern period; how in the shift from manuscript to print culture, the book became not simply a text, but a place and property, and by extension of this, how the goal of printing was not exact replication of an original text but dissemination.19 Woven throughout Orgel’s book is also a timeline of the historical evolution of reading practices, from manuscript culture to the advent of printing and the digital age. Orgel ultimately offers comprehensive analysis of how changes in reading technologies and the dissemination of texts have shaped the book and reader’s role over time.

Although not explicitly dealing with the study of marginalia as previously mentioned works have, Juliet Fleming’s work in her book Cultural Graphology: Writing after Derrida focuses on material affordances particular to the book and the pen. Her framing of the medium is considered key in understanding the annotation of texts as not just evidence of an active reader, but as an act of writing “which is material, which has the power to invent things (including selves), and which exists at the intersection of generic norms and technological affordances.”20 Fleming positions her work by expanding on the notion of “cultural graphology” that Jacques Derrida loosely proposes in his work, Grammatology, which examines the relationship between writing practices, materiality, and cultural contexts.21 Fleming engages with Derrida’s deconstructionist approach and expands upon his ideas to analyze how writing functions as a cultural and social practice through the lens of the writing culture in early modern England, particularly as it came to be influenced by the commercial development of print.22 She investigates the materiality of writing, including handwriting, typography, and inscriptions, to unveil the hidden meanings and cultural significance embedded within written texts. By examining the dynamics of writing within cultural contexts, Fleming challenges the idea that writing is a neutral tool for communication. She explores how writing practices are shaped by cultural and historical factors, emphasizing the multiplicity of meanings and interpretations that emerge from written texts.

Especially relevant to the discussion of marginalia is Fleming’s conceptualization of the “renaissance collage” which describes the reading undertaken in this period with scissors and knives, through the cutting of the page and associated processes of sewing, stitching, gluing, and filing.23 She categorises the act of cutting books for the purposes of:

Remov[ing] proscribed or offensive material from religious texts and learning materials, to obviate the labour of copying in producing commonplace books and other compilations, to reformat texts in order to rationalize the material they contained, to provide room for marginal or other commentaries, to add other material to and thereby expand a given text, to organize their own researches, and to illustrate or embellish presentation and other manuscripts with motifs cut from printed sources.24

Thus establishing this form of readers’ traces as not just the organization of written information, but also as an act of writing. For Fleming, “the cut opens, gathers and sorts; it shapes the present and introduces the future” akin to how historians of reading posit marginalia is used, as seen in Jardine and Grafton’s understanding of Harvey’s political notes on a text of ancient history, or Sherman’s notion of private and public connections within annotations. Annotation, like cutting, is not destructive, but rather a means to grow the work being interacted with. Through her exploration of cultural graphology, Fleming invites readers, and in particular, historians of reading and the book, to critically engage with the complexities of writing as a cultural practice. She highlights the significance of materiality, historical context, and philosophical underpinnings in understanding the role of writing in shaping and reflecting cultural and social dynamics.

One of the most recent works published on the study of marginalia which has heavily shaped my understanding of it is the book Early Modern English Marginalia, a series of articles compiled and edited by early modern English language and literature scholar Katherine Acheson released in 2019. Part of the Material Readings in Early Modern Culture series, it delves into both the content and material forms of early modern texts, considering marginalia as both a distinct entity for scholarly analysis and lens that can be used to view early modern history through. The book is divided into three parts, each representing a way in which the presence of marginalia inserts itself into different forms of research related to the history of reading and the book. The first section titled "Materialities" explores the promise provided by the intersection between material histories of the book and the turn to writing in marginalia studies.25 It discusses the shift from physical books to electronic ones, raising questions about annotatability and the role of early modern printed books played in this. The section includes chapters on paper production, the agency of marginalia in shaping printed works, and the consideration of object marks as marginalia. It also delves into how women writers used writing, including marginalia, to create various spaces for themselves, both physical and symbolic, within the context of early modern society. The second section, "Selves", approaches books and their margins as spaces for various forms of life-writing, where individuals inscribe their personal experiences, beliefs, and identities. It examines how early modern readers used marginalia to engage with religious, political, and personal matters, demonstrating how doing so shaped their own self-identities. The section features chapters that delve into examples such as religious conflicts during the English Reformation, clergymen's attestations to Church doctrine, aristocratic women's reading and writing habits, and the evolving ownership claims within a seventeenth-century library. Overall, it highlights the interconnectedness of individuals' lives and the narratives found within the pages of the books they interacted with. The final section is "Modes", which investigate the concept of "mode" as a product of the intersection between a genre of writing and a technology of representation.26 It delves into how marginalia exemplify this intersection, considering the expanse of its presence across multiple genres and technologies, such as printed books, handwriting, and conversation. Works in this section highlight how marginalia can be seen as collaborative authorship and how modes like Twitter mirror early modern marginalia in building intellectual communities. Ultimately, the section demonstrates how understanding marginalia as modes enhances our comprehension of their innovative and transformative role in communication, literature, and learning. In its entirety, Early Modern English Marginalia offers a comprehensive exploration of the multifaceted nature of marginalia, illuminating its significance as a dynamic lens for understanding the intricate interplay between material culture, self-expression, and modes of communication in the early modern era.

Given these understandings of marginalia, through both their presence as historical records and their physicality, the potential of dealing with these elements via digital representation suggests the richness that could be uncovered by exploring them with methods which embrace this format. The multifaceted nature of marginalia becomes even more so when a digital layer is added, opening doors to innovative modes of analysis and interpretation through data-driven investigations into patterns that might otherwise remain hidden.

3.2 Presence in Physical and Digital Archives

3.2.1 How is Marginalia defined?

Before discussing the presence of marginalia within the archive, it is important to understand how marginalia itself is defined. In the broadest sense of the word, marginalia encompasses anything left in the peripherals of a text, with the word deriving from the Latin margō (“border, edge”) which evolved into the Medieval Latin neuter plural of marginālis (“on the periphery”).27 However, those who study marginalia typically seek to shape the meaning of it further, within the context of their own and others’ research. In her 1994 analysis of annotations present in copies of Caxton’s Royal Book, Elaine E. Whitaker proposed that marginalia tended to fall into the following three categories:

- Editing

- Censorship

- Censorship

- Affirmation

- Affirmation

- Editing

- Interaction

- Devotional Use

- Devotional Use

- Social Critique

- Social Critique

- Interaction

- Avoidance

- A. Doodling

- B. Daydreaming28

- Avoidance

Providing further context to these categories, she noted that readers would edit their texts by covering sections (A) or emphasising sections with a variety of both standard and idiosyncratic marks (B). Whitaker defines interaction with the text by the reader accepting a passage and noting how it applies to their own lives (A), or appropriating it as a critique of someone or something else (B). She then outlines avoidance as being a subversive act, in which the reader used their text for something like the practice of penmanship (A) or recording thoughts that are not relevant to the text (B).29 In a similar vein, Carl James Grindley in his analysis of late medieval and early modern copies of Piers Plowman put forward the following classifications for printed and written marginalia in texts:

- TYPE I, which comprises marginalia that are without any identifiable context;

- TYPE II, which comprises marginalia that exist within a context associated with that of the manuscript itself; and

- TYPE III, which comprises marginalia directly associated with the various texts that the manuscript contains.30

Grindley greatly expands on these classifications with specific sub-types assigned to each class. Type I includes marginalia such as doodles or sample texts– “short works, in either poetry or prose, which were added in an unplanned if not haphazard manner to a non-related existing text”– similar to Whitaker’s category of “Avoidance”.31 Type II marginalia encompasses the space between marginalia unrelated to the text it uses as its foundation and that which reveals the “active” reader. While not providing explicit commentary on the text at hand, this form of marginalia might offer introductory materials such as brief descriptive notes identifying the main theme or subject of a work, or marks of attribution that indicate the origin of a text. Type III marginalia tend to be the form of marginalia which historians such as Sherman and Orgel anchor their textual analysis to; this marginalia is substantial and “implies a coherent reader response to a particular text” which in turn elicits the most substantial sub-classification by Grindley. He breaks down Type III marginalia into the following:

- Narrative Reading Aids, which denote annotations that include aids to understanding the narrative present in the text, such as citations, translations, or summation.

- Ethical Pointers are a demonstration of ethical positionality.

- Polemical Reponses are associated with a social or political issue in the text, either deliberating over the situation at hand or applying the situation to one that is contemporary with the commentator.

- Literary Responses entail the reader engaging in diaglogue with the text, through commenting on linguistic, humorous, ironical, allegorical, metaphorical, or other “poetic” elements of the text.

- Graphical Responses feature systemised forms of graphic shorthand or added punctuation.

With his breakdown of classification, Grindley sought to aid the historian in answering the questions of what a particular reader was interested in, how the reader organize a text, what reactions readers had to particular passages, and if the annotations followed any general themes.32 In the three categories which Brayman Hackel outlines in her survey of English readers, she seemingly only considers Grindley’s Type III classification as being “marginalia”:

Early modern readers’ handwritten marks in books generally fall into three classes, each of which exposes a set of attitudes about books and reading. Marks of active reading (deictics, underlining, summaries, cross-references, queries), to which I refer loosely as marginalia, suggest that the book is to be engaged, digested, and re-read. Marks of ownership (signatures, shelf marks, proprietary verses) distinguish a book as a physical object, to be protected, catalogued, inventoried, and valued. Marks of recording (debts, marriages, births, accounts) seem to reside somewhere in between: like ownership marks, they suggest that the book has physical value; like readers’ marks, they convey that the book is a site of information. For each of these three kinds of notes, the book takes on a different role: as intellectual process, as valued object, and as available paper.33

For Brayman Hackel, “active” reading and evidence of intellectual process appear to be prerequisites to a mark being classified as “marginalia”. Unlike previous systems of classification and as Orgel points out, Brayman Hackel also does not leave space in her classifications for the ubiquitous “irrelevant markings” despite discussing these findings in her analysis of copies of Arcadia34:

Fragments of verse, lists of clothing, enigmatic phrases, incomplete calculations, sassy records of ownership: some of these traces merely puzzle. Drawings and doodlings in other copies hint at other associations or preoccupations: a shield painted in watercolors, impish faces peering out from the margin, geometric figures on a flyleaf, a mother and child on a blank sheet. Pens are not the only objects that have left impressions in these books; pressed flowers survive in two volumes, and the rust outlines of pairs of scissors betray the forgetfulness of the binders, presumably, of two other copies. But other marks do fall into larger patterns, joining hands across several volumes. Fifty-six percent of the books carry marginalia or scribbling on flyleaves, most commonly in the form of penmanship practice, emendations, underlinings, and finding notes.35

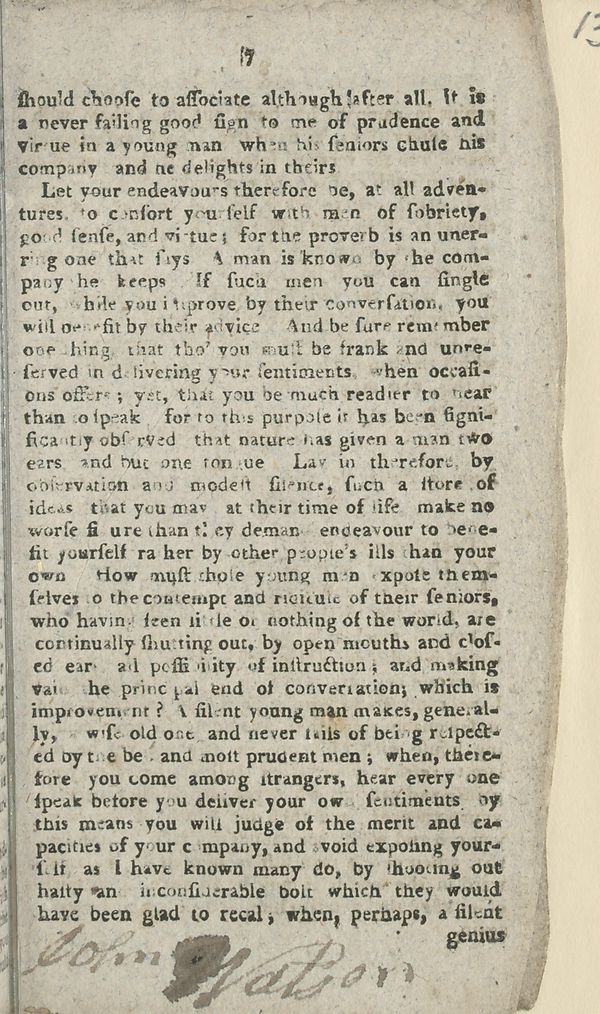

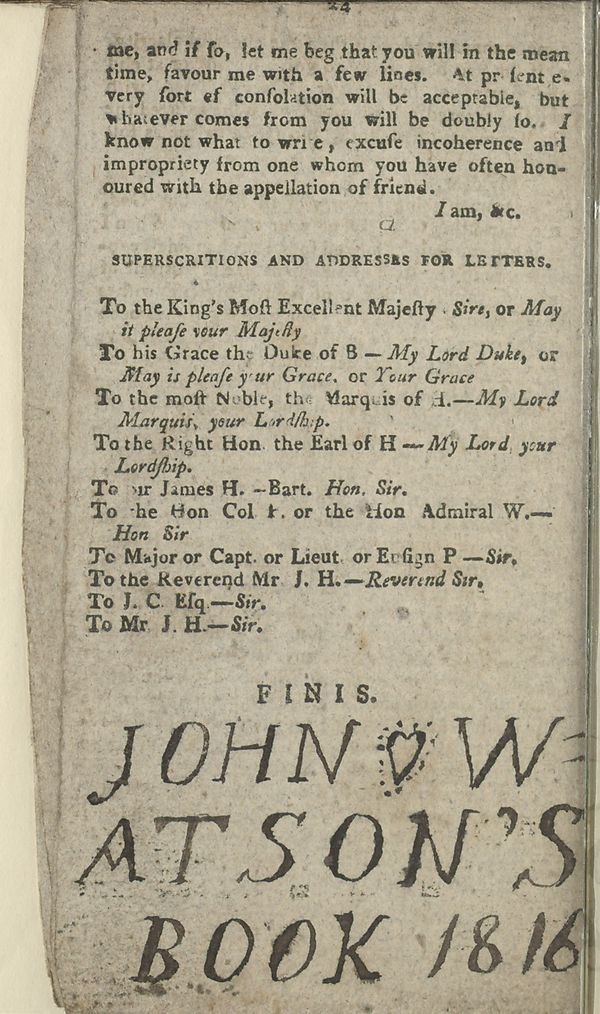

What is and is not classified as marginalia outlines a framework– both one theorised to be that of the composers, and one that the historian may follow when analysing their marks. These marks that Brayman Hackel excluded from her framework of marginalia have been conceptualized by other scholars as “graffiti”; Jason Scott-Warren draws upon Fleming’s work in considering the material affordance of that which has been marked– these impromptu inscriptions are ones which emphasize the availability and visibility of the writing surface. Fundamentally, “graffiti” is evocative of the person who created it, the place they put it, and the documentation of a relationship between them.36 One of the most common forms of graffiti found in early modern books is “sassy records of ownership” as Brayman Hackel calls it, the recording of names, present not in a conventional sense of simply marking ownership of the text at hand, but strewn throughout the text, written repeatedly, in a way similar to how a graffiti artist may tag buildings throughout their city. For example, in a copy of the chapbook The Letter Writer held in the National Library of Scotland’s archive, annotator John Watson appeared to have used the pages to practice his signature, marking a number of pages with his name in both cursive and print (see Figure 1).

Figure 3.1: John Waston’s signatures. Printed by C. Randall, The Letter-Writer, 1807, National Library of Scotland, http://digital.nls.uk/104186662.

Sherman expands on the value of these markings well; in studying the annotated texts found in the Huntington Library, he noted how a majority of the annotations had no obvious connection with the text they accompanied, yet they “nonetheless testified to the place of that book in the reader’s social life, family history, professional practices, political commitments, and devotional rituals.”37

The archives which I draw from for this project’s case study will be expanded upon much more extensively in a later section, yet at this moment it is valuable to consider how marginalia is represented in them; what is counted as marginalia in the context of digital collections? The Archaeology of Reading (AoR) collection existed as a project to digitize and compile select annotated books from the libraries of prolific early modern readers John Dee and Gabriel Harvey, and to then transcribe, and occasionally translate, the marginalia on pages it is present so that it can be easily read alongside the printed text and archival item’s metadata.38 In studying these transcriptions, AoR includes any category of textual marginalia of which there is plenty due to the interactive approach Dee and Harvey took to reading. The more elaborate graphical responses such as manicules and florilegia are also made note of, however symbols such as small crosses or underlinings are excluded despite (or perhaps because of) their abundance. These symbols are often excluded from broad analysis of marginalia despite being a constant presence found almost exclusively in the margins of text– they are marginalia in the truest sense of the word. Conversely, the Early Modern Annotated Books collection from UCLA’s William Andrews Clark Memorial Library only identified that the book, or, collection of pages, had marginalia within them, but did not indicate which pages and by extension, offer any transcription of the marginalia. What is defined as marginalia here is entirely up to the reader of their archive.

3.2.2 Physical and Digital Presence

In considering the archive, marginalia have always been present yet their presence has always been contentious. Early modern readers were taught to read with tool to write in hand; they were not just encouraged to annotate their books, but taught how to do so in their schooling.39 Marginalia was a way for readers to connect with their previous knowledge, literature, and each other as the book circulated, yet as the concern exists at present, there was concern even during the early modern period about, as Sherman phrases it, “dirty books”. Books with marginalia were considered marred, being no longer in the pristine condition that they were in fresh off the printing press, which was a largely desired state for collectors from the early modern period into the 20ht century.40 The notable exception to this rule being annotations made by famous figures such as William Shakespeare or Francis Bacon, which added value to the books, that is, if they were identified before being “cleaned”. Due to the desire for virgin books, annotated books were often “restored” in a way that removed the marginalia present through methods such as the bleaching of page edges or by cutting out the margins of these books then rebinding them. This is all to say, the marginalia present in physical archives around the world is either skewed to portraying to the reading and writing practices of a select educated and famed class of society, preserved due to the perceived significance of the books they owned, or accidental by-products of archiving used books. This historical lack of intentional curation of marginalia has made the exploration of them a challenge; there are no single physical archives that gather marginalia en masse to be studied, they are more often discovered organically when studying the content of early modern books, or by paging through large collections of early modern books with the intention of searching for marginalia specifically. Since marginalia is largely left uncatalogued, it remains difficult to find even during the advent of the digital archive.

In 2008, reflecting on the laborious process he undertook when producing his expansive text on early modern marginalia, Sherman wrote in the afterword of Used Books:

Databases and facsimiles of the sort described above are primarily concerned with giving us access to accurate and attractive informational content and with helping us to make our way around it (a goal generally known, in the computer and information sciences, as “usability”). Their emphasis on “interactivity” notwithstanding, they have not yet imagined us doing much with or to books beyond turning their pages and have not yet found ways to preserve our marks—much less to improve them or to educate us about the markings of those who turned pages before us.41

As of the year I am writing this, 2023, despite many technological advances in the realm of the dead hand of the pdf and skeuomorphic design, Sherman’s statement holds largely true within the bounds of digitized cultural heritage collections. AoR is the only project I discovered in the process of research that places marginalia in the context of “those who turned pages before us,” yet its functionality does not go beyond turning from page to page, and simple manipulations such as zooming in and out. The one project I did come across in which 3D models were constructed from the pages of manuscripts found at Lichfield Cathedral had marginalia make an accidental appearance.42 As a whole, marginalia is still not easily discoverable even with digitised archives outside of projects dedicated to identifying marginalia, which are also few. Partly, this is due to the way digital technologies have evolved to prioritize text (not margins), and also partly due to metadata standards which shape digital archival items failing to adapt their form to the unique affordances that digitisation offers; metadata standards for digitisation focus on documenting details about the physical object and were developed from the same cataloguing standards that excluded marginalia originally. AoR explains this problem as one they faced during the development of their project. Upon digitizing the books of Dee and Harvey, AoR then needed to select a standard to use when creating the digital documents. Initially, they looked at the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) standard, formed by a consortium which collectively develops and maintains a standard for the representation of texts in digital form; the TEI is largely considered a high standard of documentation for representing digitised texts, yet upon further investigation AoR found that TEI left no option for recording annotations featured on a text, thus they ultimately had to create their own bespoke digitisation schema for their project which centered around this form of text.

As I will demonstrate, there are now computational methods that could be used by archives to discover marginalia in their collections and in turn, an opportunity to automatically enhance their metadata. However, these methods require an extensive amount of “examples” of marginalia in order to begin identifying it; these examples are difficult to accumulate due to the lack of any indication of marginalia within digital archives, thus creating a cycle in which marginalia continues to be an elusive presence.

3.3 On Object Marks and Machines

Acheson’s book raises a number of historical, cultural, and theoretical questions about books and their readers, many of which could be explored further through greater access to more obscure, both literally and figuratively, research materials such as marginalia. Adam Smyth’s contribution to Early Modern English Marginalia particularly emphasises this; in his chapter, he sought to identify current traits in recent works on the history of marginalia which bring to the surface a number of questions, paradoxes or gaps, through the analysis of object traces in early modern books.43 These traits-as-problems which Smyth uses to illustrate the value of attending to object traces can also be used to understand the value of integrating machine learning methods, particularly object detection, into the study of marginalia.

The history of reading has often revolved around individual readers, even as early modern studies broadly have shifted away from this and towards to the coterie, and, in more recent years, to the network as the unit of cultural analysis.44 This focus on biography has meant that studies of marginalia have tended to connect book annotations back to the individual who created them at the expense of other ways of organizing marginalia, such as by genre. Further expanding on the neglect of genre, the use of biography as the frame for analysing marginalia books has meant that scholars, preoccupied connecting the page marks to the reader’s life and identity, have spent less time seeking to establish fundamental histories of the marks themselves, such as where the conventions for marking books came from; in seeking to link marginalia to writing outside of the host text, Smyth posits the questions, “What category of mark or intervention are they? What is the larger group in which they belong?”45 The tether which holds the study of marginalia to biography is at least in part due to the issues of discoverability that marginalia presents. Although more reliably discoverable than the trace object marks which Smyth features in his work, marginalia still demand time to be found whether the host being searched is physical or digital. Identifying genre or larger categories which marginalia can be viewed through or belong to require wide reading of numerous sources in order to be defined. Undoubtedly, the work of studying and defining marginalia to date has been an impressive feat, but as noted by the historians who performed this feat, it is immensely time consuming and difficult process if the marginalia one seeks to study is not already gathered, which is often the case. The automated detection of marginalia that my tool permits allows for large and diverse corpora to be evaluated for the presence of marginalia with little supervision and more efficiently than a researcher is able to sift through these works manually; following this quick process of identifying marginalia, researchers may then focus on the discovery of genre through analysis of the object detector’s output.

Another trait Smyth identifies in the study of marginalia is the assignment of the reader as “active”. Rather than being “passive”, readers read with an idea of practical application in their world and the future, “reading as intended to give rise to something else.”46 Smyth refers to the inverse of an active reader, an inactive reader, as being found present in unmarked pages, yet I propose an inactive reader could also be defined as one who dismisses the content of the book in favour of its materiality, as something that can be repurposed as a diary or catalogue of debts (cite wigmaker’s pages). It is this genre of “inactive” reading that I attempt to find in the following case study using an object detection model applied to the NLS collection of early modern chapbooks printed in Scotland.47 By microscopely analysing the marginalia of over 3000 works made for popular consumption, trends in how these booklets were used as something more than just the entertainment found in their contents can be identified.

Gabriel Harvey and George Charles Moore Smith, Gabriel Harvey’s Marginalia (Stratford-upon-Avon: Shakespeare Head Press, 1913).↩︎

Katherine Acheson, ed., Early Modern English Marginalia (New York: Routledge, 2019), 3, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315228815.↩︎

Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton, “"Studied for Action": How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy,” Past & Present, no. 129 (1990): 36, https://www.jstor.org/stable/650933.↩︎

Heidi Brayman Hackel, Reading Material in Early Modern England: Print, Gender, and Literacy (Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).↩︎

Brayman Hackel, Reading Material in Early Modern England, 84–99.↩︎

Brayman Hackel, Reading Material in Early Modern England, 257.↩︎

William H. Sherman, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhgzw.↩︎

Sherman, Used Books, xiv.↩︎

Stephen Orgel, The Reader in the Book: A Study of Spaces and Traces (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2015), 24, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/oculcarleton-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4310757.↩︎

Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Corrected ed (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 87.↩︎

Juliet Fleming, Cultural Graphology: Writing After Derrida (University of Chicago Press, 2016), 28.↩︎

Oxford English Dictionary, “Marginalia, n., Etymology” (Oxford University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7050641376.↩︎

Elaine E. Whitaker, “A Collaboration of Readers: Categorization of the Annotations in Copies of Caxton’s Royal Book,” Text 7 (1994): 235, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30227702.↩︎

Carl James Grindley, “Reading Piers Plowman C-Text Annotations: Notes Toward the Classification of Printed and Written Marginalia in Texts from the British Isles 1300-1641,” in The Medieval Professional Reader at Work: Evidence from Manuscripts of Chaucer, Langland, Kempe, and Gower, ed. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton and Maidie Hilmo (Victoria, BC: English Literary Studies, 2001), 77.↩︎

Brayman Hackel, Reading Material in Early Modern England, 138.↩︎

Brayman Hackel, Reading Material in Early Modern England, 159.↩︎

Jason Scott-Warren, “Reading Graffiti in the Early Modern Book,” The Huntington Library Quarterly, 2010, 366, https://www.proquest.com/docview/763492186/abstract/832093B897F1447APQ/1.↩︎

Sherman, Used Books, xiii.↩︎

“Archaeology of Reading,” September 2014, https://archaeologyofreading.org/.↩︎

Noah Adler and Justin Hall, “Matt 28:19 - 28:20, Pg 141,” Manuscripts of Lichfiled Cathedral, accessed August 21, 2023, https://lichfield.ou.edu/file/14428.↩︎